Facial eczema (pithomycotoxicosis) is a disease in grazing animals caused by spores of the fungus Pithomyces chartarum. In alpacas, early exposure to the spore toxin leads to liver damage and photosensitisation; prevention focuses on spore count monitoring, pasture management and especially zinc supplementation.

Te

Korito

Alpacas

Facial Eczema

Facial Eczema (Pithomycotoxicosis).

Why facial eczema is serious

This liver disease of grazing animals, including alpacas, sheep, cattle, deer and goats is caused by ingestion of spores from the pasture fungus Pithomyces chartarum.

These spores contain the mycotoxin sporidesmin which causes oxidative injury to the liver and bile ducts. Damage to the biliary system prevents normal excretion of bile pigments and the chlorophyll breakdown product phylloerythrin, leading to secondary photosensitisation of the skin.

Facial eczema causes severe animal suffering and significant economic loss. In New Zealand alone, production losses attributed to facial eczema are estimated at approximately NZ$332 million annually. Although facial eczema occurs worldwide, it is particularly common in New Zealand due to the high prevalence of toxin-producing strains of Pithomyces chartarum. Alpacas are more sensitive than sheep to sporidesmin toxicity, likely because there has been little or no evolutionary selection pressure in their native environment.

How facial eczema develops

After several days of warm, humid conditions with night-time temperatures above 13 °C, the fungus grows on decaying plant material at the base of the pasture sward [22]. Grazing animals ingest spores while feeding.

Once ingested, sporidesmin is absorbed from the gut and transported to the liver, where it causes severe damage to bile ducts and surrounding liver tissue. Obstruction of bile flow may occur, resulting in jaundice and accumulation of phylloerythrin in the bloodstream. Exposure of the skin to sunlight then triggers painful photosensitisation [4].

Affected animals may show skin irritation, swelling of the face and ears, drooping ears, swollen eyes, restlessness, frequent urination and a strong preference for shade. Importantly, by the time visible symptoms appear, significant and often permanent liver damage has already occurred. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and confirmed by blood testing for elevated γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels.

Long-term consequences

Sporidesmin toxicity frequently results in permanent liver damage. While the liver can regenerate to some extent, it rarely returns to full function, leaving affected animals at increased risk during subsequent facial eczema seasons.

Pregnant females with severe liver damage may die shortly after giving birth, as the foetus had partially supported maternal liver function. Re-exposure to even low spore levels can trigger severe disease due to potentiation. In sheep, subclinical facial eczema is associated with reduced fertility and body condition; similar effects are likely in alpacas.

Prevention of facial eczema:

Spore numbers in the grass swards indicate how toxic it will be if eaten and so spore counting is a reliable indicator. There are many commercial and local veterinary services available for determining spore counts in samples taken from paddocks. A number of videos are available online showing methods for taking samples. These sample bags should be taken to a veterinary practice or farm supply business for sending to the testing laboratory. Other local area spore counts may also be available there. Aggregated counts for areas nationwide can be viewed on the Awanui Veterinary website and also show previous facial eczema seasons. The graphs shown after accessing the lab-portal are real-time and indicate the percentage of received counts above the 30,000 spores/gram of material. Counts in excess of 30,000 spores/g sample are regarded as hazardous to all stock.

Protecting your alpacas from these fungal spores cannot be overemphasised. There are three main elements to achieving this as shown in the panel.Protecting your alpacas

1. Preventing growth of the fungus

- Spraying paddocks with fungicides

Ideally, this should be done before the start of the season as the fungicide kills only the vegetative fungus cells and not any spores already produced. Carbendazim sprays have been shown as effective in controlling sporulation throughout the facial eczema season [21]. Your vet or farm supply store can advise on the appropriate product and application method. Alpacas may graze the sprayed paddock after a number of days as specified in the product description. The treatment provides a level of protection for around 6 weeks unless there is significant rainfall. Reapplication of the fungicide to each paddock will be necessary and taking samples for spore counts will indicate when the protection is fading. - The topping of pastures must be avoided as it increases the amount of dead plant material at ground level.

2. Reducing exposure to the toxin

- Stock should be rotated around paddocks with good growth on them and moved on before eating them right down.

- Paddocks with minimal remaining grass should be closed off until good regrowth has occurred. Heavy rain helps by washing spores into the ground.

- Alternative feedstuffs should be freely available during danger periods, especially good quality hay, as it reduces the proportion of pasture material consumed.

3. Using zinc to minimise the harm

- Zinc supplementation is an effective prophylaxis against sporidesmin toxicity, as zinc reduces sporidesmin-driven oxidative damage to bile duct epithelium.

- The incorporation of zinc oxide into alpaca nuts (kibble) is the only practical way of achieving consistent zinc intake. Zinc kibble is widely available from farm supply stores during the facial eczema season.

- Adding zinc salts to drinking water is ineffective because alpacas consume small volumes of water and may refuse water due to the bitter taste of zinc.

- Slow-release zinc boluses should not be used in alpacas, as rumen breakdown can result in rapid zinc release and potentially toxic blood levels. Oral zinc sulphate slurries should not be used for the same reason.

The role of copper

Key point: Copper increases the severity of facial eczema by amplifying sporidesmin-induced oxidative liver damage, while zinc reduces this effect.

Sporidesmin is inherently toxic, but its toxicity is greatly increased when it undergoes oxidative reactions in the liver in the presence of free copper. Evidence indicates that the toxic effect of sporidesmin is due to its ability to generate highly reactive superoxide radicals. Zinc ions interact with sporidesmin and inhibit the formation of these radicals.

The principle behind zinc supplementation is relatively simple. Zinc and copper are absorbed from the gut via shared transport mechanisms. When sufficient zinc is supplied, these carriers are preferentially occupied, reducing copper absorption. Conversely, excess dietary copper interferes with zinc absorption.

Although the liver normally stores copper safely bound to specific proteins, this balance can be disrupted during the facial eczema season. Damage to bile ducts impairs copper excretion, leading to copper accumulation in the liver and compounding liver injury.

The implications during the facial eczema risk period are:

- Avoid feeding mineral mixes containing copper.

- Be cautious with pelleted feeds unless their copper content is known.

- Avoid all other forms of copper supplementation, including injections and drenches.

This advice may seem counter-intuitive, but if liver damage has occurred and copper excretion is impaired, additional copper greatly increases the risk of toxic accumulation and delayed copper poisoning.

The FE seasonal pattern

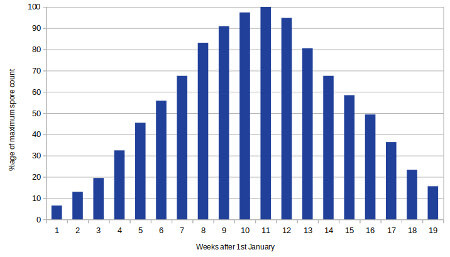

The image below illustrates a typical seasonal pattern of pasture spore counts during the facial eczema risk period. Peak spore levels usually occur in March or April, although the timing and magnitude vary widely with seasonal conditions. Spore counts also vary substantially between farms, paddocks, and even within a single paddock, highlighting the importance of local monitoring.

In New Zealand, the facial eczema season usually starts in early January. Given that it takes about two weeks for the blood zinc levels to rise to a protective state, the feeding of zinc-containing nuts should begin at New Year. Much depends on the weather in your area because if the ground is very dry and there is not likely to be any rain in the next week or so, starting dosing may be delayed. Long range weather forecasts can help here.

Zinc Kibble Calculator

Dosing with zinc

Introduction of the zinc kibble should be gradual - initially adding some to normal alpaca nuts and steadily increasing the proportion added over about 10 days until the correct level is reached. Supplementation with 2g of elemental zinc per 100kg live weight per day is recommended by the feed manufacturers and scientific literature. Provided here is a calculator to work out how much should be fed to an alpaca of a given weight. This assumes kibble being fed which contains 8g of supplemental zinc per kilo.

From observations in other ruminant species, excessive consumption of zinc for extended periods of time is known to lead to mild pancreatitis and copper deficiency. Because of this, a maximum period of 100 days is recommended for sheep and cattle. Unfortunately, there are no studies with alpacas into this dosing period so rightly or wrongly, the same recommendation has been followed. It can be seen from the graph that the 100 days of dosing expires during April when spore counts are still elevated so most owners extend this period. The onset and severity of the facial eczema seasons vary so having grass samples tested and keeping a close watch on spore counts is essential.

Please note that the peak of spore production during the FE season can be at any time in the 16 week risk period. In 2021 there were in fact two peaks (in weeks 9 and 14) whereas 2022 peaked only in week 6. In particularly bad FE years, an extended period of dosing with zinc pellets and feed supplementation will be needed - the reversible side-effects of copper deficiency and mild pancreatitis are a far better outcomes for the alpaca when compared with death through liver failure.

Facial Eczema – Common Questions

Facial eczema is caused by ingestion of spores from the pasture fungus Pithomyces chartarum. These spores contain the toxin sporidesmin, which damages the liver and bile ducts and leads to photosensitisation of the skin.

Alpacas are more sensitive to sporidesmin than sheep, likely because they did not evolve in environments where this fungus is present. As a result, even moderate spore exposure can cause severe permanent liver damage.

There is no cure for the liver damage caused by sporidesmin. By the time visible signs such as facial swelling or skin irritation appear, significant liver injury has usually already occurred. This is why prevention is critical.

Regular pasture spore counting is the most reliable way to assess risk. Blood testing for elevated GGT levels can confirm liver damage before obvious clinical signs develop.

In New Zealand, zinc supplementation usually begins around New Year. Because it takes around two weeks for blood zinc levels to reach a protective range, timing should be guided by local weather patterns and seasonal spore trends.

Regular pasture spore counting is the most reliable way to assess risk. Blood testing for elevated GGT levels can confirm liver damage before obvious clinical signs develop.

Yes. Maintaining good pasture cover, avoiding overgrazing, rotating stock, providing supplementary feed and avoiding pasture topping all reduce spore ingestion. Fungicide spraying can also be effective when used correctly. See Protecting your alpacas.

Extended zinc supplementation can cause mild pancreatitis and copper deficiency, but these effects are usually reversible. In high-risk seasons, prolonged zinc use is far safer than the potentially fatal consequences of untreated facial eczema. See Zinc Kibble Calculator.

References.

Most of the literature below can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted link. Some links will access the appropriate web page from which the article can be downloaded but others will immediately start downloading the full reference.

4. Boyd, E. (2016). Management of Facial Eczema. M.Vet. Stud., Massey University.

21. Sinclair, D.P. and Howe, M.W. (1967). Effect of thiabendazole on Pithomyces chartarum (Berk. & Curt.) M. B. Ellis. N.Z. J. Ag. Res., 11(1): 59-62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.1968.10431634

22. Mitchell, K. J., Thomas, R. G. and Clarke, R. T. J. (1961). Factors influencing the growth of Pithomyces chartarum in pasture. N.Z. J. Ag. Res., 4(5-6): 566-577. DOI: 10.1080/00288233.1961.10431614

Popular Page Links